The El-Alamein Military Museum was built in 1965 to cater to visiting veterans and their families. Both the winners (British) and losers (Italian and German) received equal exhibit space, and as a neutral caretakers of the battleground, the Egyptian authorities kept their judgements over motives to a minimum and proffered equally neutral platitudes of valor for all. At no point did the then non-aligned Socialist Gamal ʿAbdel Nasser regime ever consider the battle or World War II more generally as having anything to do with Egypt. Its military had been kept on sentry duty in the delta and major cities, and all wartime British promises of treaty renegotiation over the Suez canal occupation had been betrayed by 1947.

Collective memory — and more concretely, the state’s presentation of history — always reflects the events of the past through the political and social lenses of the present. What is authentic to a certain public, or what the state will propose as authentic, changes over time. From 1952 to 1967, as Yoav Di-Capua describes in his excellent Gatekeepers of the Arab Past: Historians and History Writing in Twentieth Century Egypt, the modernist development-oriented post-colonial regime downplayed the events of the Muhammad ʿAli dynasty and British occupation, instead creating ritual performances for its reforms designed to make Egyptian society feel it was making history in the present.

With the failure of the modernist socialist project, and of the Egyptian military in the 1967 war, the state realigned itself with the capitalist world in the 1970s under Anwar El-Sadat and began to look for a new historical narrative to correspond to this political reality. The mixed success of the October 1973 war at winning back Egyptian control of a patch of Sinai from Israeli occupation was the seed from which a garden of new rituals and symbols bloomed. The date of the canal crossing, October 6, became a national holiday, and it has been used to name a major satellite city, a central bridge in Cairo and in many other places besides.

Larger monuments with specific messages — say, war museums — take time and initiative. Sadat’s term in office was filled with the Israeli peace negotiations and an abortive political liberalization. Such projects were left to his successor, Hosni Mubarak. Luckily for Mubarak, one of the great military museum builders of the late 20th century was looking for friends by the late 1980s.

This sign is posted on a wall outside the museum, built in Muhammad ʿAli Pasha’s enormous palace in the Citadel, in English and Korean but not Arabic. What it doesn’t say is that the North Koreans also built or renovated every military museum in the country in this period, including the 1973 War Panorama in Heliopolis, the 1973 War Museum in Port Said, and the El-Alamein War Museum (on which more anon).

The timing of the construction of these museums is not hard to understand. Egypt had just emerged from ten years of estrangement with the Arab world. The Arab League, which it once dominated, expelled it for signing a unilateral peace agreement with Israel in 1979, and Iraq ascended to a more dominant role in pan-Arab affairs. But Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 resulted in the angry turn of the Gulf Arab states against him. Egypt’s eager participation in the US coalition — in which the US allowed Egyptian troops to be the first across the Saudi border to liberate Kuwait — heralded its return to the Arab League. The time was right for a triumphant declaration of a global vision of Egyptian military history that rehabilitated Muhammad ʿAli as the founder of the modern Egyptian nation, with strong Arab connections. Moreover, the impending collapse of the Soviet Union and international Communism meant North Korea was looking for any friends it could find. The Christian Science Monitor has a decent roundup of Egyptian-North Korean relations in the Mubarak era.

I can’t help laughing at the use of “creative team” in the translation on the plaque at the Citadel, as if the North Korean army were an up-and-coming Madison Ave. advertising firm. However much the Egyptians decided they needed or wanted the help of the North Koreans to make these new museums, the overall result was an absurd intrusion of socialist realism onto good old neoliberal chauvinism. The effect is particularly inappropriate for Egypt, considering the Egyptian public’s unruly, humorous attitude towards its political leadership (even if there has always been a strong undercurrent of respect for the stability that leadership brought, if the Shafiq vote is any indication).

I take as an example the genre set piece, “Adoration of the Leader”:

This is the mural at the entrance of the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum in Pyongyang. A young Kim Il Sung, with a modest single medal, leads his army and proletariat forward into a bright future after the country’s independence with the armistice in 1953. Of course, the children, the symbols of that future, are just at hand. Keep an eye on those pastel balloons.

Apparently Kim Il Sung had made contacts with the Syrians as well in this period. This image of Syrian President Hafez al-Assad is at the entrance of the Syrian October 1973 (Tishreen) War memorial. An orgy of balloons, the kids and the pigeons all indicate this painting was in the same workshop at the same time as the Egyptian one below. But the Syrians got a groovy 3-D effect with the floor mosaic in the painting coming right down some steps and into the room.

Here’s the Egyptian version. Sitting at the center of the huge foyer entrance to Muhammad ʿAli’s palace, it is the first large image one sees entering the museum. The legend at the bottom reads “Egypt, The Honour, Genuineness and History.” Slightly more austere, it actually looks like it could be a real military parade. Mubarak is marching in a line as equals with his military commanders, not waving, and the kids are off to the side. Having visited Syria, I always remarked that Mubarak never built himself up as much of a charismatic leader as the Assads did. There are still plenty of balloons. But wait! Something odd is going on with that flag…

That’s right, the day we visited the museum in mid-August last year (2011) the consensus of the museum staff was to put the Egyptian flag normally standing to the side of the painting over the face and body of Mubarak at the center of the painting. This inversion of the original intent of the image produces a surreal/dadaist effect — Ceci n’est pas un president. Unfortunately for whoever thought to do that, the building is a temple to Mubarak, and in order to cover his face everywhere in it, one would need to buy up every Egyptian flag currently on sale in Tahrir Square.

The detail in rest of the painting is a fascinating window into the imagination of the Egyptian “technical advisers” to the North Korean creative team. It is a veritable Where’s Waldo of stereotypes of Egyptian society. We’ve got some lower class rural women wearing colorful outfits and authentic, pre-Hijab headscarves. There’s also a Coptic priest reaching to touch Mubarak as if he were Justin Bieber, and hadn’t in fact been stirring up communal suspicion of the Christians for the past dozen years of his rule. The dominant figure in this side of the picture, with some irony, is a Salafi-looking gent in a white galabeya and with a dopey grin on his face. The early nineties were the peak of the state’s war on radical Islamist groups, most of which were based in Upper Egypt, although Jihad, the group that assassinated Sadat, was based in Cairo. Even though Mubarak would send shock troops to Imbaba in 1993 and lock up 5,000 guys just for looking like this guy, of course he made it on to the painting. To his right, we have a technocrat or Infitah-era investor-executive holding what could be the blueprints to a new Hardees in Mohendiseen. It looks even like Saddam Hussein himself (far left) made it out to congratulate Mubarak.

The detail in rest of the painting is a fascinating window into the imagination of the Egyptian “technical advisers” to the North Korean creative team. It is a veritable Where’s Waldo of stereotypes of Egyptian society. We’ve got some lower class rural women wearing colorful outfits and authentic, pre-Hijab headscarves. There’s also a Coptic priest reaching to touch Mubarak as if he were Justin Bieber, and hadn’t in fact been stirring up communal suspicion of the Christians for the past dozen years of his rule. The dominant figure in this side of the picture, with some irony, is a Salafi-looking gent in a white galabeya and with a dopey grin on his face. The early nineties were the peak of the state’s war on radical Islamist groups, most of which were based in Upper Egypt, although Jihad, the group that assassinated Sadat, was based in Cairo. Even though Mubarak would send shock troops to Imbaba in 1993 and lock up 5,000 guys just for looking like this guy, of course he made it on to the painting. To his right, we have a technocrat or Infitah-era investor-executive holding what could be the blueprints to a new Hardees in Mohendiseen. It looks even like Saddam Hussein himself (far left) made it out to congratulate Mubarak.

On the left side of the picture, there’s more of the same, in distinct types. In the middle is “Ibn al-Balad,” a stock character that represents the goodness and simplicity of the Egyptian fellah (peasant) and thus the national character altogether. He was the mascot of the biggest-selling weekly magazine in Egypt during the 30s and 40s, Al-Ithneyn wal-Dunya, and would frequently show up to make satirically simplistic questions of the politicians of the day (at right).

On the left side of the picture, there’s more of the same, in distinct types. In the middle is “Ibn al-Balad,” a stock character that represents the goodness and simplicity of the Egyptian fellah (peasant) and thus the national character altogether. He was the mascot of the biggest-selling weekly magazine in Egypt during the 30s and 40s, Al-Ithneyn wal-Dunya, and would frequently show up to make satirically simplistic questions of the politicians of the day (at right).  Four more women are present at the front of the crowd. One of them is wearing a visible gold cross and has her hair uncovered. The schoolgirl is wearing a uniform and also has her hair uncovered. The other two women are wearing different forms of the contemporary Hijab headcoverings. The overall effect is a subtle message that the state is OK with these public signs of female Muslim piety, but within the boundaries of postpubescence and ostensible tolerance for Christian women’s appearance. Notably, there are no upper class or bare-headed Muslim women I could identify, i.e. nobody like former first lady Suzanne Mubarak.

Four more women are present at the front of the crowd. One of them is wearing a visible gold cross and has her hair uncovered. The schoolgirl is wearing a uniform and also has her hair uncovered. The other two women are wearing different forms of the contemporary Hijab headcoverings. The overall effect is a subtle message that the state is OK with these public signs of female Muslim piety, but within the boundaries of postpubescence and ostensible tolerance for Christian women’s appearance. Notably, there are no upper class or bare-headed Muslim women I could identify, i.e. nobody like former first lady Suzanne Mubarak.

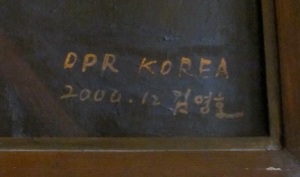

The North Korean creative team produced dozens of paintings for the Citadel Military Museum alone. They put this 15-foot long painting of the 1882 nationalist revolution led by Colonel ʿOrabi in a narrow hallway between two rooms, so this raked angle was the best shot I could get of it. Even though the plaque outside said the project occurred in the early nineties, the painting signatures indicate the North Koreans were making additions well into the 2000s.

The North Korean creative team produced dozens of paintings for the Citadel Military Museum alone. They put this 15-foot long painting of the 1882 nationalist revolution led by Colonel ʿOrabi in a narrow hallway between two rooms, so this raked angle was the best shot I could get of it. Even though the plaque outside said the project occurred in the early nineties, the painting signatures indicate the North Koreans were making additions well into the 2000s.

The creative team didn’t just do paintings, either.

The creative team didn’t just do paintings, either.  Here’s a fabulous bronze statue of Mubarak emerging from a large boulder in front of a diorama of the air battles in the 1973 war. The relative success he had as chief of staff of the air force during the war secured his promotion to vice-president. It later boosted his image in his weak first decade as president.

Here’s a fabulous bronze statue of Mubarak emerging from a large boulder in front of a diorama of the air battles in the 1973 war. The relative success he had as chief of staff of the air force during the war secured his promotion to vice-president. It later boosted his image in his weak first decade as president.

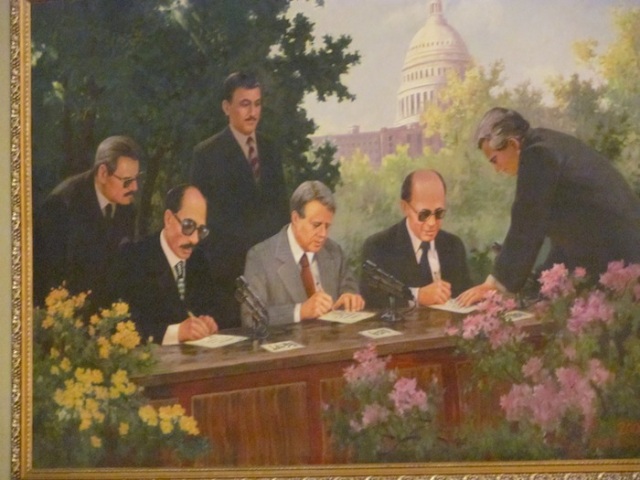

Of course, at the end of the 1973 hall, we have an exhibit explaining and legitimating the Camp David peace process. Sadat and Menachim Begin are signing the assorted treaty paperwork with their sunglasses still on. I hope they can finish up before those monster azalea bushes swallow them whole.

Of course, at the end of the 1973 hall, we have an exhibit explaining and legitimating the Camp David peace process. Sadat and Menachim Begin are signing the assorted treaty paperwork with their sunglasses still on. I hope they can finish up before those monster azalea bushes swallow them whole.

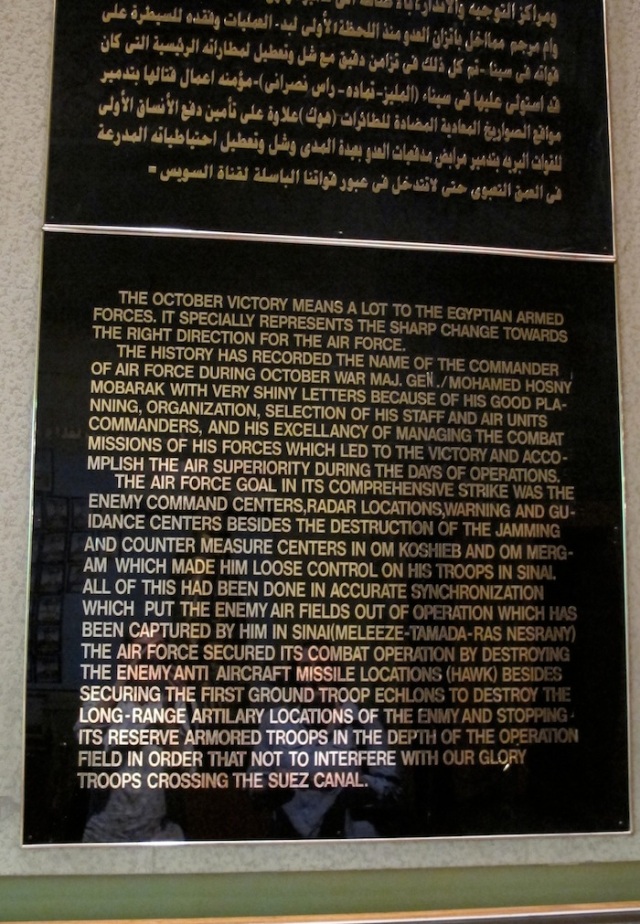

For foreign visitors, the museum is crippled by poor English translations of already propagandistic bombast, resulting in a shiny string of poor grammar and run-on sentences. We missed capturing the original Arabic of the phrase below, which MAY have reduced its hilarity.

For foreign visitors, the museum is crippled by poor English translations of already propagandistic bombast, resulting in a shiny string of poor grammar and run-on sentences. We missed capturing the original Arabic of the phrase below, which MAY have reduced its hilarity.

Please excuse my extended detour into Cairo’s Egyptian Military Museum. In part III, I will return to El-Alamein for an investigation into the North Korean/Mubarak overhaul of the military museum there for the 50th anniversary of the battle in 1992.

Nicely done. I’ve added a link here: bit.ly/1973panoramas.

Pingback: The “Genuine History” of Egypt in the Second World War (Part III) | Eric Schewe

your post is very interesting. I have a few questions you may be able to help me with in relation to the war in the Middle East mainly the suez canal area and transit camps in that area. I hope you can help and look forward to your response.